When Lucash Uniack was in first grade, he loved to learn but hated reading. Because he has a condition in which his eye muscles are weaker than usual, he struggled with tracking words on a page. “I’d get headaches, and I’d read really slowly,” he remembers.

Now 13, Uniack is a voracious reader—and it’s largely thanks to the Washington Talking Book and Braille Library.

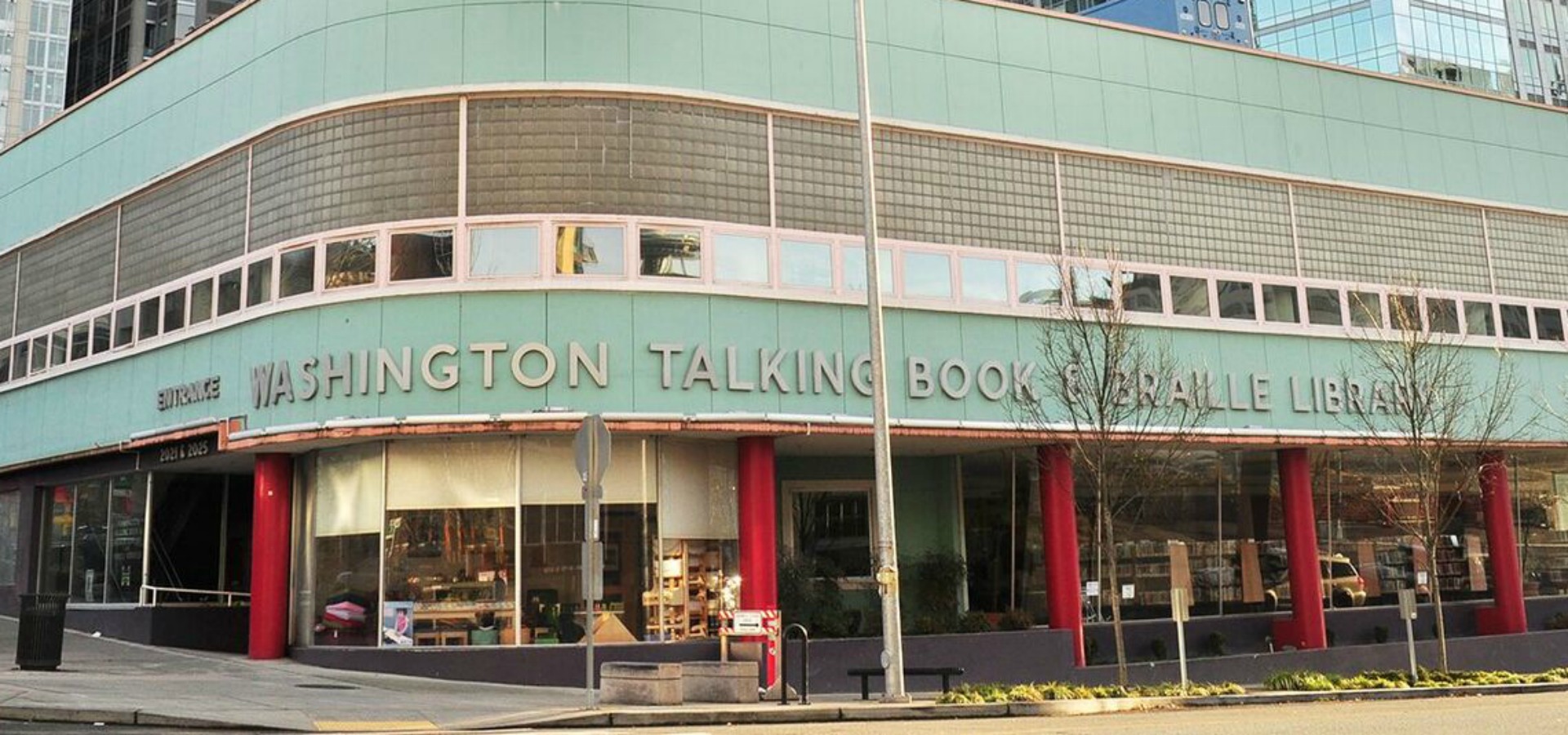

The WTBBL in South Lake Union, a program of the Washington State Library and the Office of the Secretary of State, is part of a national network of libraries dedicated to helping anyone unable to read standard print material due to issues such as blindness, visual impairment, deaf-blindness, or a physical disability that prevents holding a book or turning pages.

While most patrons receive their selections for free via the U.S. Postal Service, those who live in the area can visit the library, located inside an old car dealership on the corner of 9th and Lenora. Last year, the library assisted more than 10,300 walk-in visitors.